Hello from Impact Delta.

In this issue, we look at how governance is sometimes taken for granted when it's not under a microscope. We'll also look at BlackRock's recent DEI report, as well as Microsoft's 2021 environmental report, in advance of their upcoming 2022 release. Finally, we'll look at whether carbon prices have an impact on share prices of companies that have regulatory exposure to the Emissions Trading System (referred to as “ETS system”) in Europe (spoiler alert, they do).

Good governance is most prevalent in the sunlight - Most investors that focus on ESG spend most of their time enhancing 'E' and 'S' efforts, with the view that 'G' is very well in hand. Indeed, the research on the benefits of diverse boards (and management teams) is clear that this approach leads to better performance and returns. However, the application of best practices and what is considered good governance is not as widespread as is often assumed. A recent report in the Yale Law Journal highlights how the governance practices vary between Fortune 500 companies and their smaller counterparts. The “governance gap” is material and in "smaller, less-scrutinized corporations, the adoption of governance arrangements is less systematic and often significantly departs from the norms set by larger companies." This likely reflects that companies do not default to best practices for governance absent additional regulatory or investor pressure, which is more pronounced for larger companies.

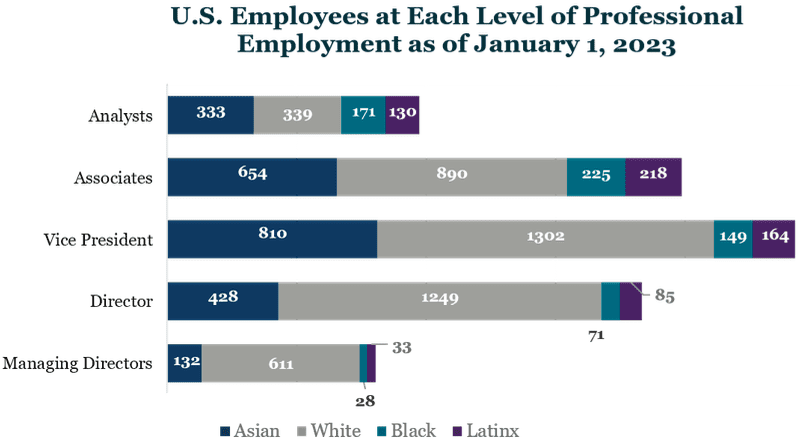

DEI is a challenging issue to hold on to - We give BlackRock full credit for having time bound and quantifiable objectives for its DEI work. As impressive is their use of an independent third party (Covington) to hold them accountable. BlackRock recently released its diversity report, with findings that highlight the challenges in building a diverse financial services company. The data highlighted that the challenge for diversifying their workforce is less of a candidate pipeline issue, than it is a retention and promotion issue (a common refrain, discussed in our January Newsletter). The chart below highlights this challenge as well as the report's findings that "In 2022, attrition rates of Black senior leaders nearly offset increases in Black senior leader hiring and led to senior Black representation staying nearly flat for the year. Attrition has also had a significant impact on overall Latinx representation which, combined with Latinx recruiting, has resulted in an overall increase in Latinx representation of just 0.5 percentage points during the same time period."

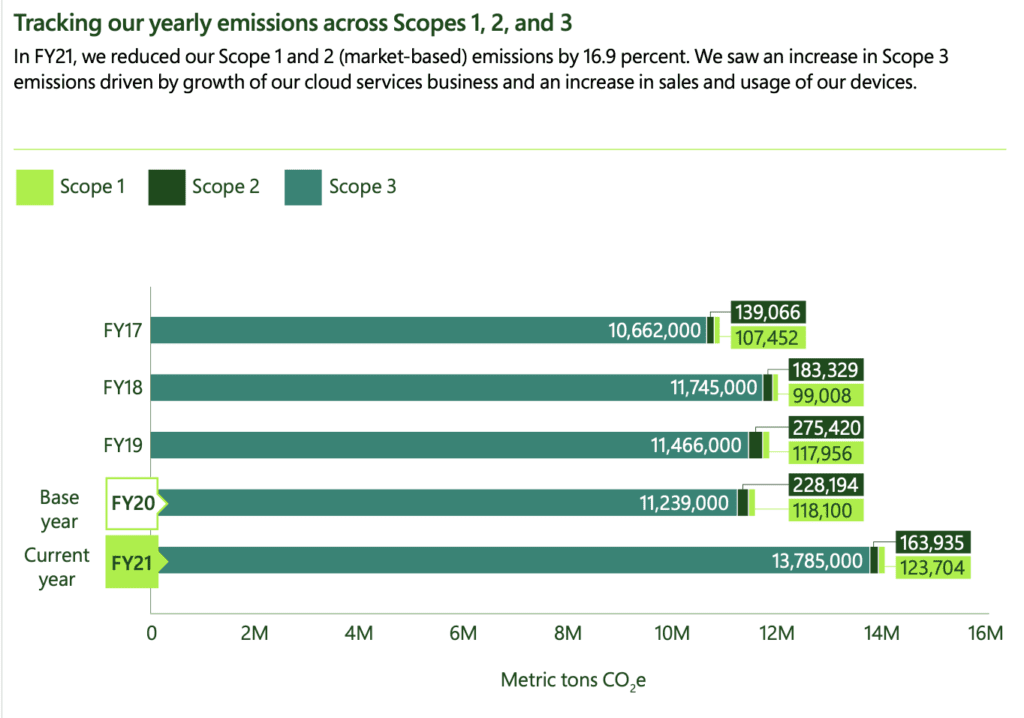

It ain't easy being green (and growing rapidly) – Companies in tech sector have, in general, done far better than those in other industries in seeking to identify and address their environmental footprints. Among the tech crowd, Microsoft has impressed us with their efforts around climate and the environment, seeking to be net zero by 2030 and to have offset all the carbon the company has ever generated by 2050. As part of this work, they have been at the forefront of improving carbon markets and offset solutions. However, the results that were published in the 2021 report outline some of the challenges in driving absolute reductions while experiencing growth. With the 2022 report likely to be released in the coming weeks, we'll be looking to see if they have found more ways to reduce their environmental footprint, while continuing to support the growth of their businesses. As AI, the 'cloud', and other digital tools continue to expand, it will be increasingly challenging to reduce emissions in absolute terms, and Microsoft will need to rely more heavily than expected on offsets to achieve net zero.

Carbon influences stock prices – at least in Europe - With Microsoft investing significant capital to get to net zero, the question becomes: is it's actually worth it? A recent study of European securities tried to parse out the impact of the carbon price on share prices. The study just focused on regulated entities that had carbon emissions allowances through the EU ETS market. This is a “cap-and-trade scheme, in which participants face limits on total emissions and are simultaneously offered allowances (either for free or through an auction process). Companies that reduce emissions well below their caps can sell their allowances in the market; those that need additional allowances must buy them. This as the effect of creating a price for carbon. The most recent phase of the ETS (“Phase 3” from 2013-2020) saw carbon prices rise from EUR5 per metric ton, to over EUR30.

As intuition would suggest, the research found that those companies that had an excess of carbon allowances saw their shares prices increase when carbon prices increase, while those companies that were short of allowances saw share prices decrease when the carbon price increased. Indeed the "study indicates a high level of informational efficiency of financial markets, with stock traders responding in real time to changes in carbon prices, taking account of disclosed information on carbon permit coverage." In less happy news, the paper also studied total corporate emissions, whether they are regulated by the EU ETS or not. Here (and also as intuition might suggest) companies “with a significant shortfall in emissions permits do lower their emissions in the EU [but] they do not lower their emissions globally.” Hence, the EU rules have likely had the effect of lowering corporate carbon emissions, but this effect has been only regional.